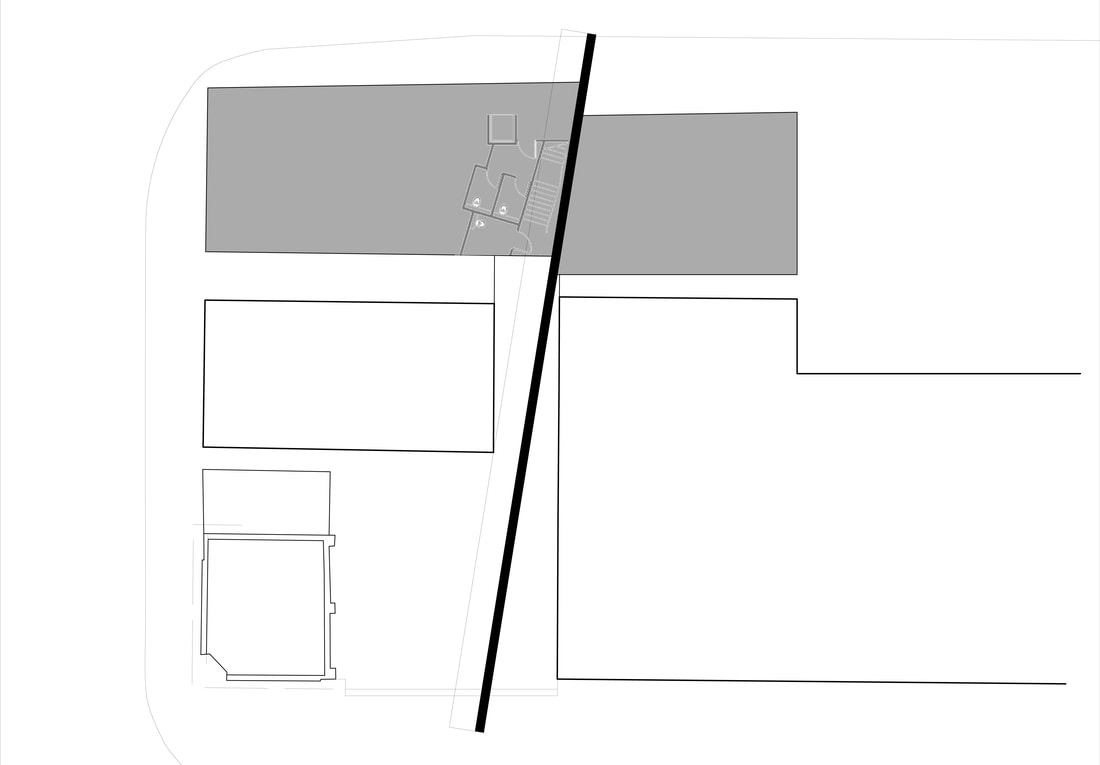

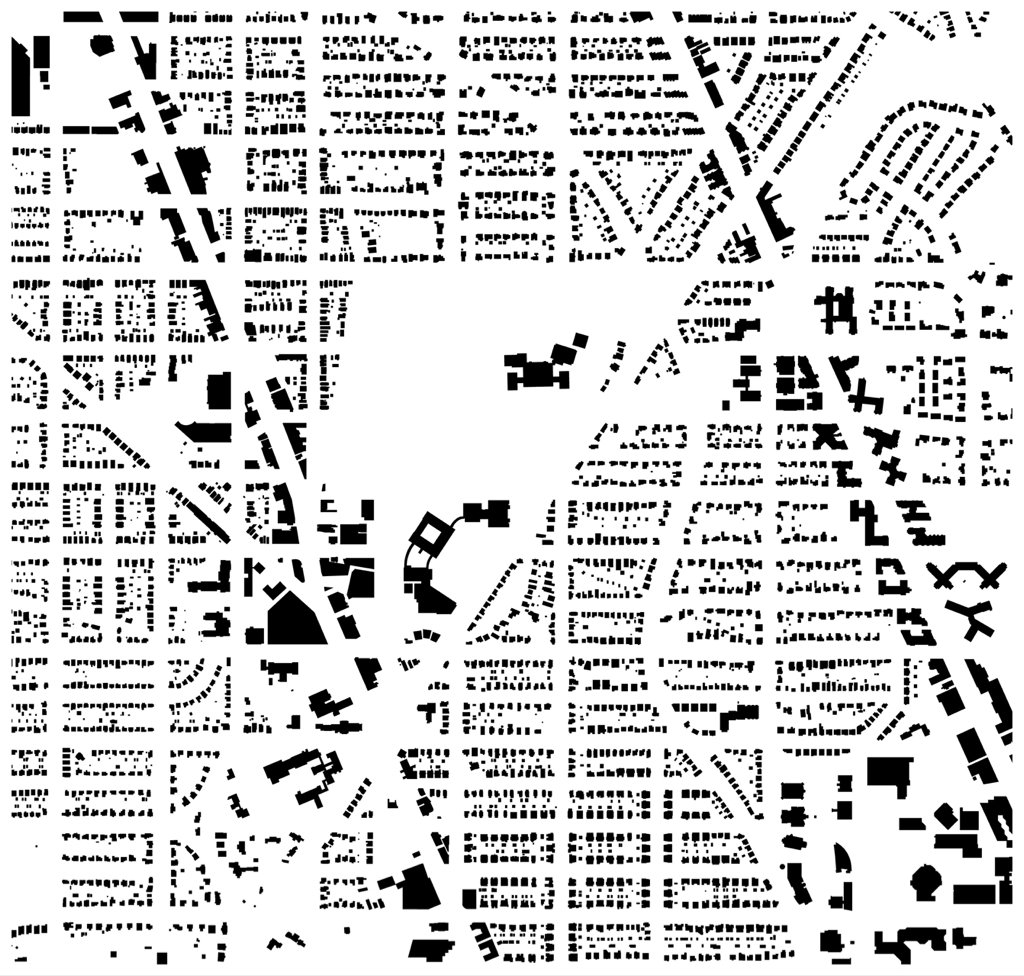

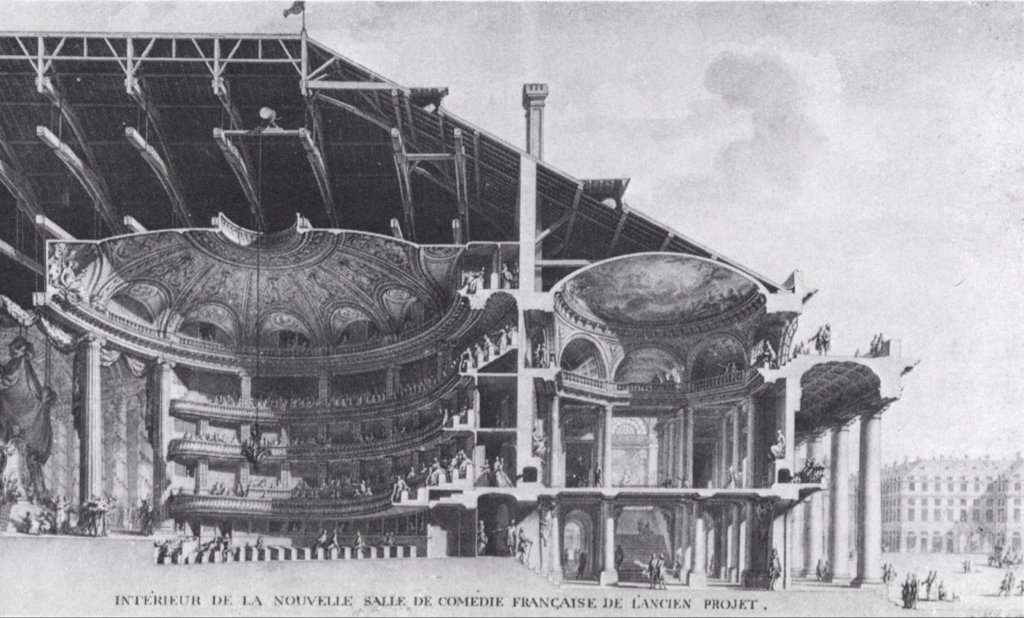

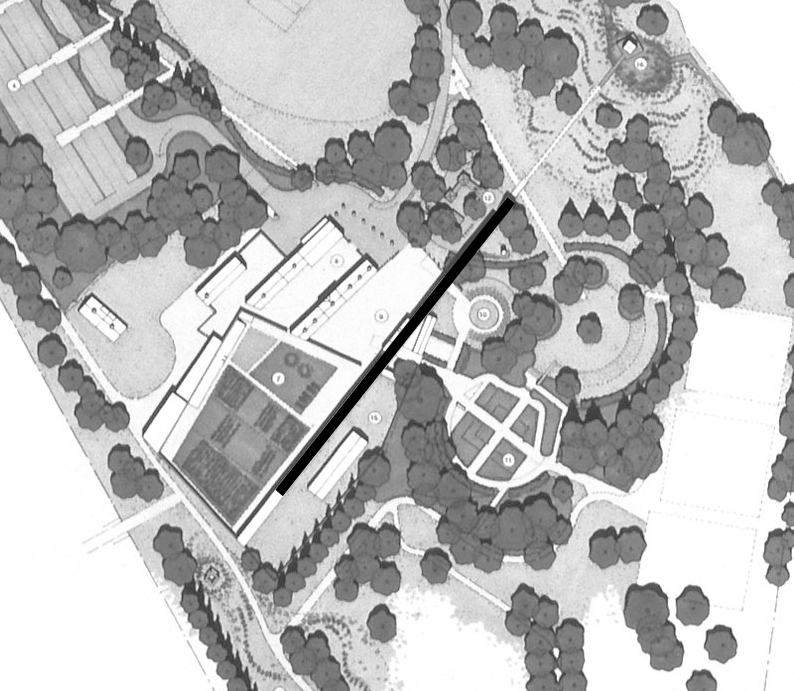

I watched a Peter Eisenman lecture a couple of days ago and he said something which got me thinking. He always does. One of my favourite points from a few years ago was how sculpture and architecture swapped their position somewhere around the beginning of the twentieth century. Traditional sculpture had no particular location — set on a plinth, a kind of universal level separated from the ground — ground as earth. Modernism in Architecture transformed the ground into a universal plane, a never-ending grid — a surface which slid under architecture, taking with it the very notion of place — and the edifice of inside and outside. In reverse symmetry Modernism in sculpture saw the plinth evaporate as works became site specific, contextual, even environmental — think of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty. Sculpture left the Plan.

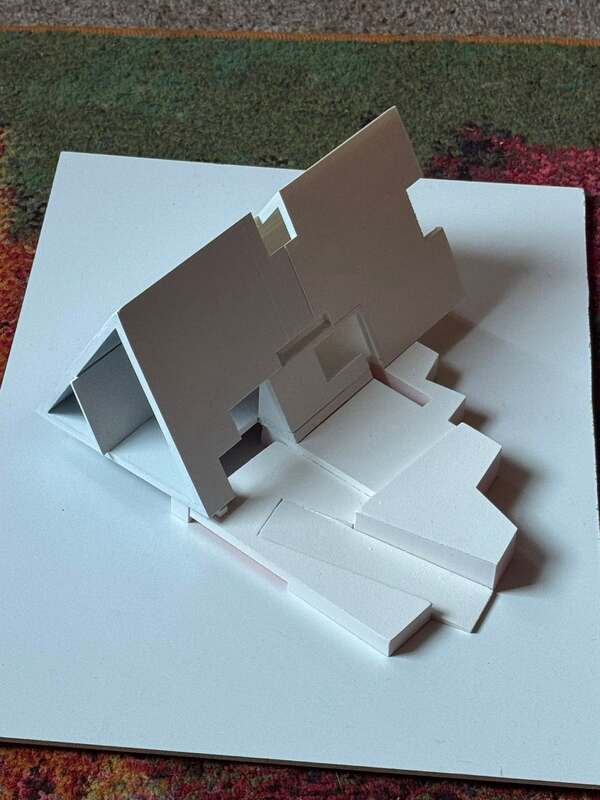

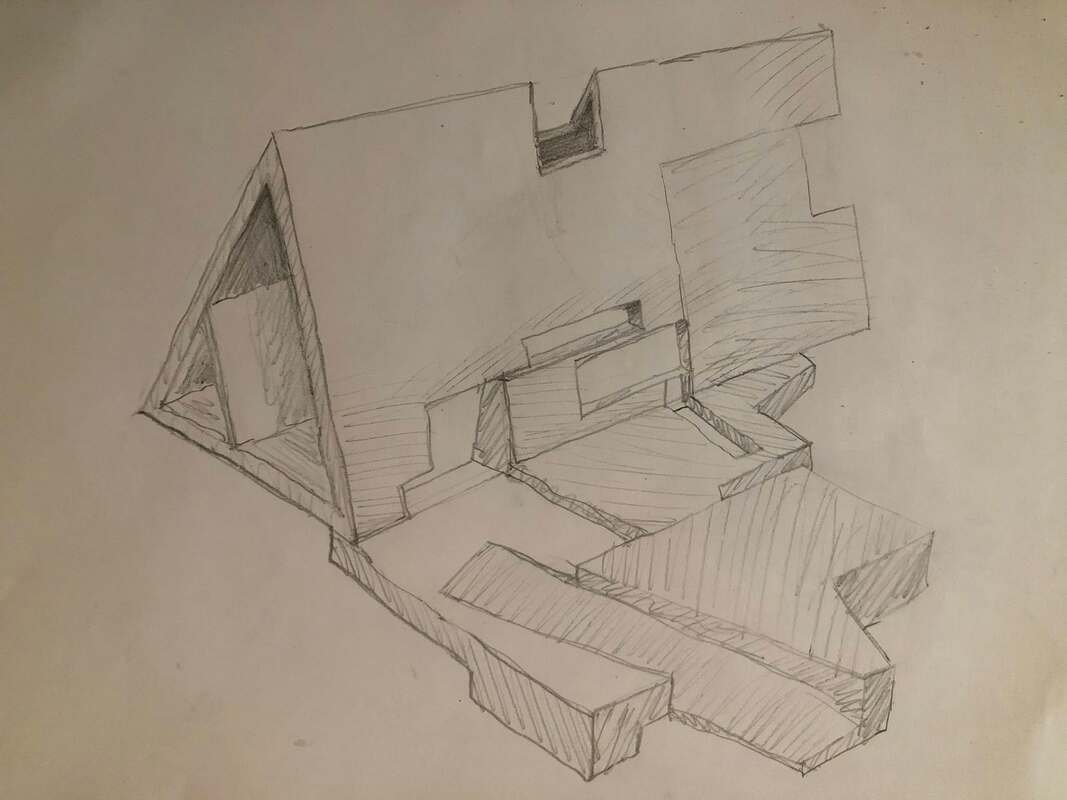

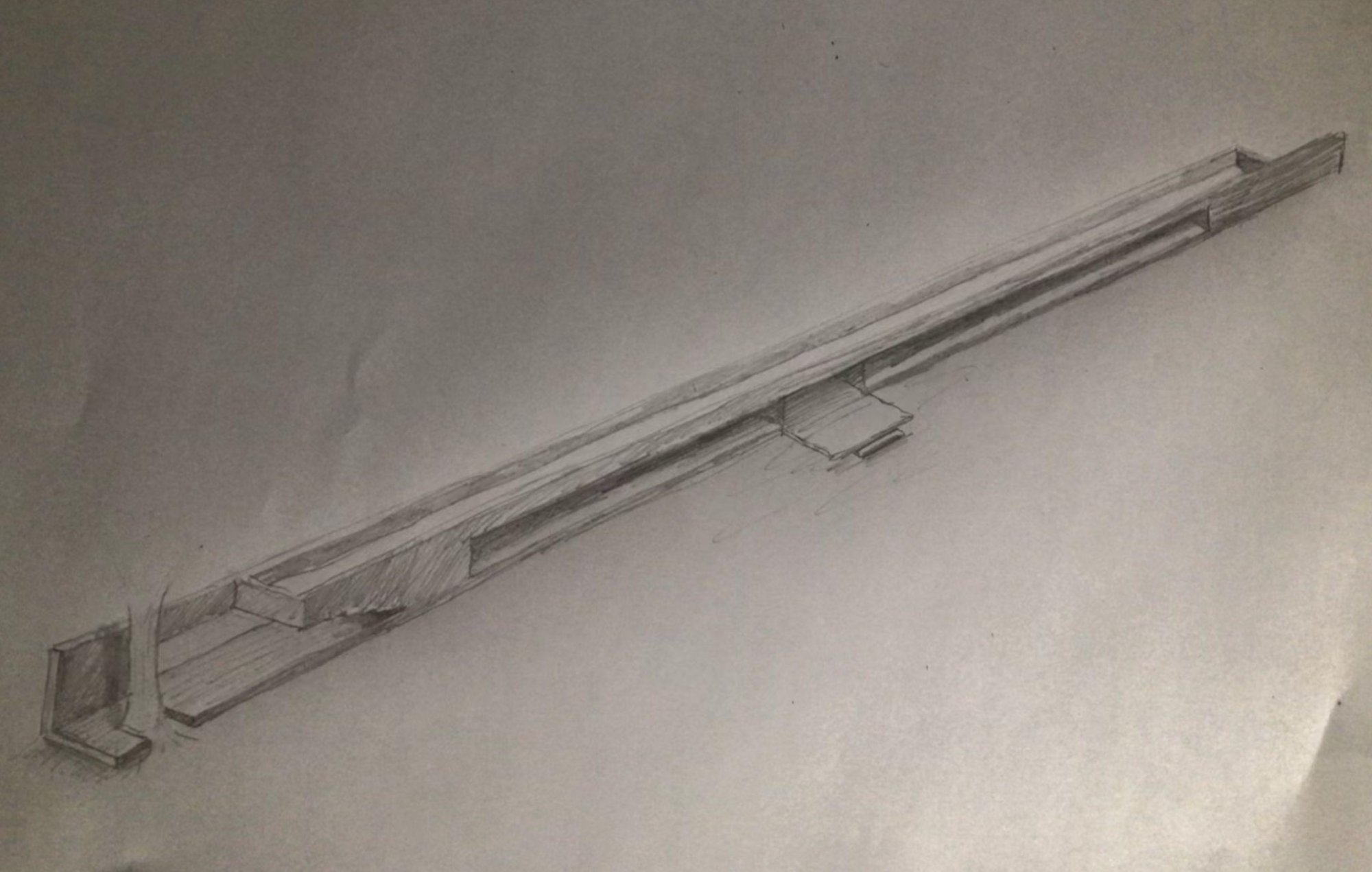

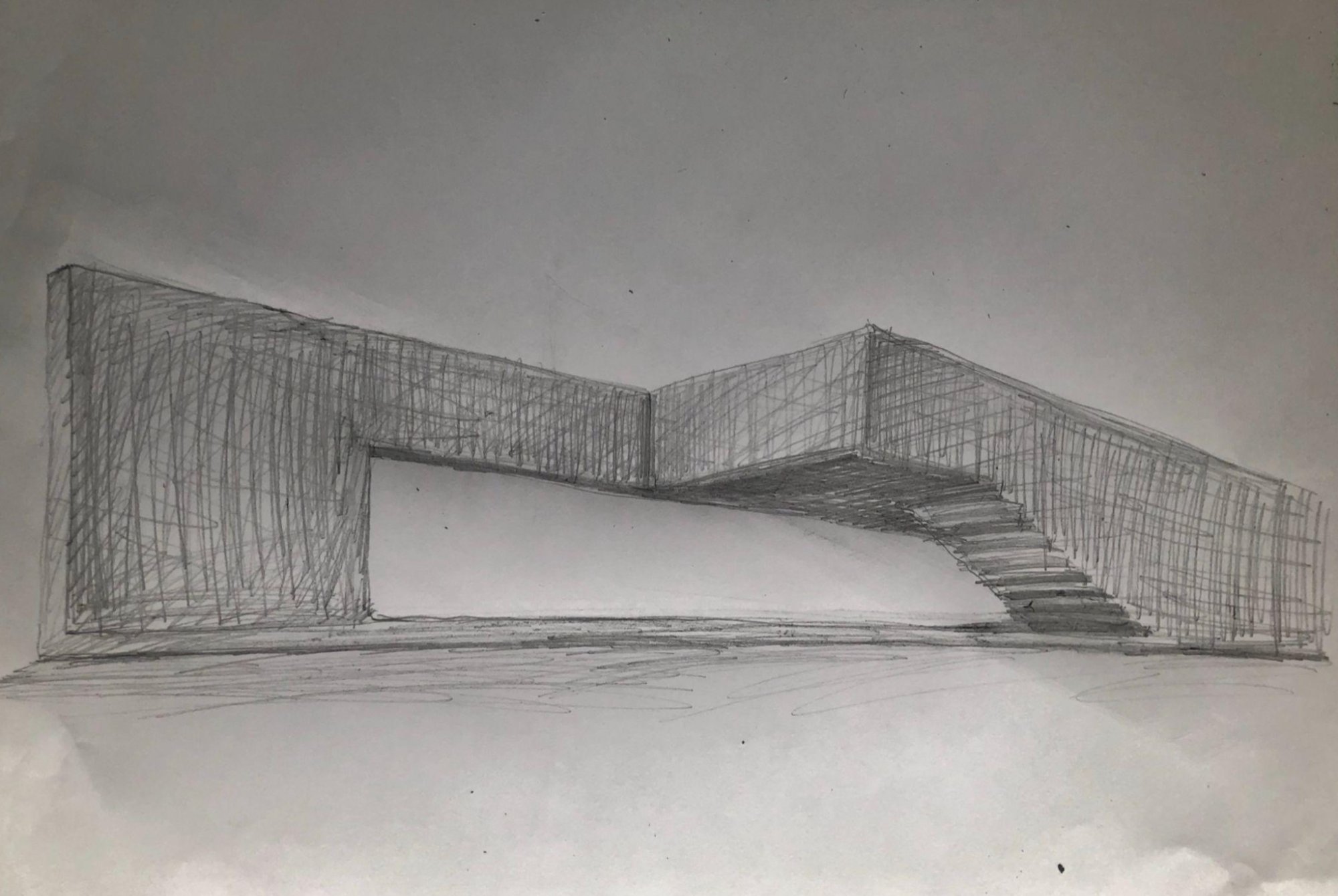

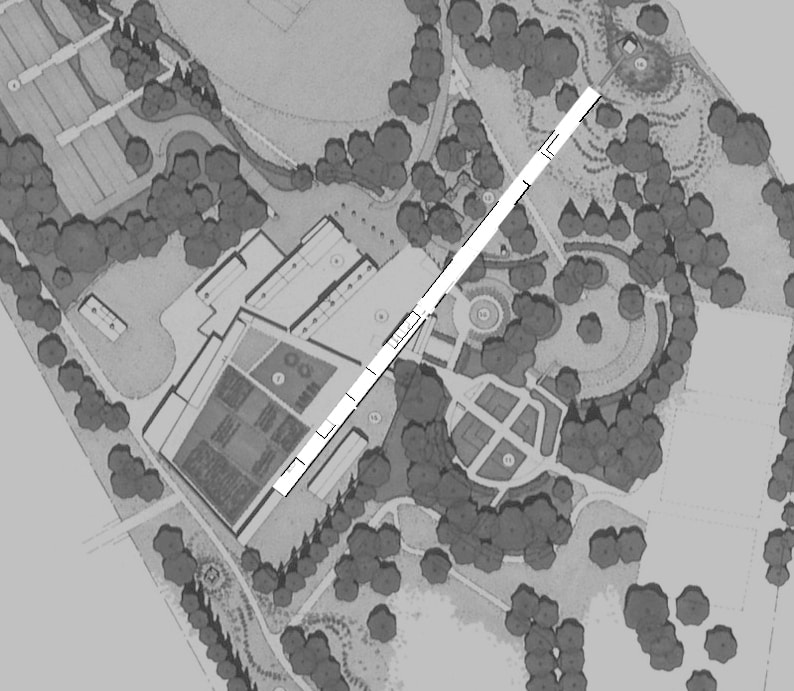

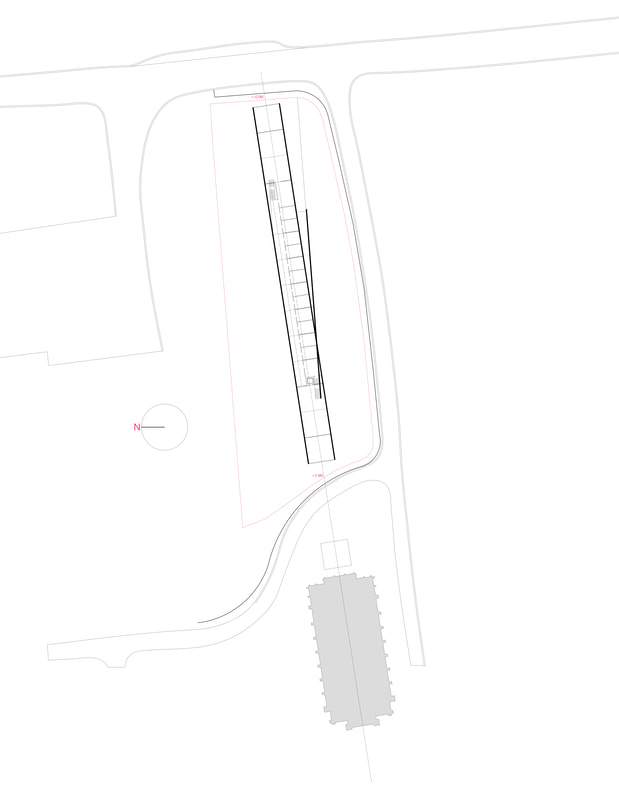

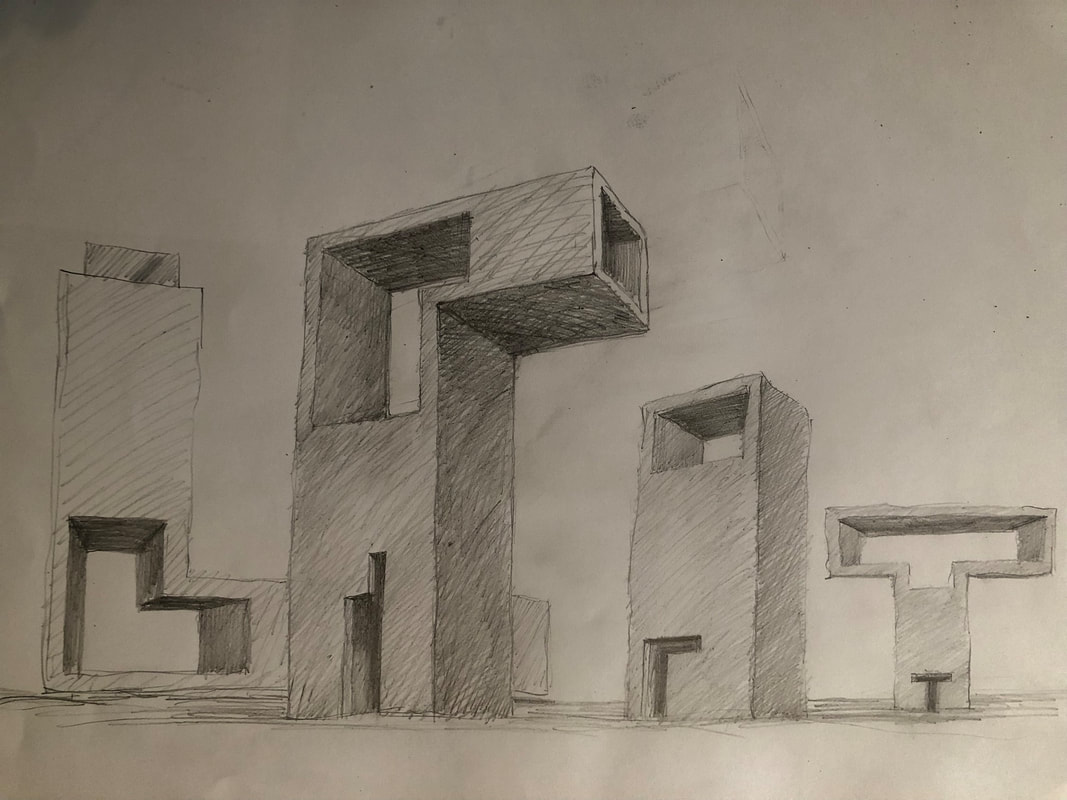

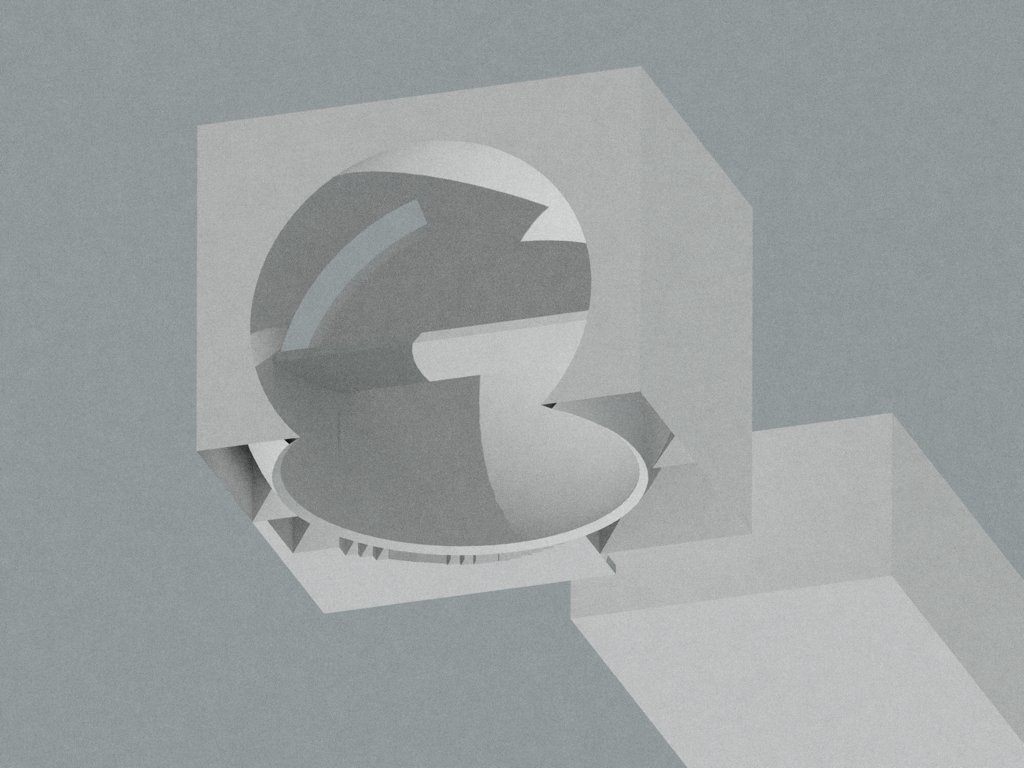

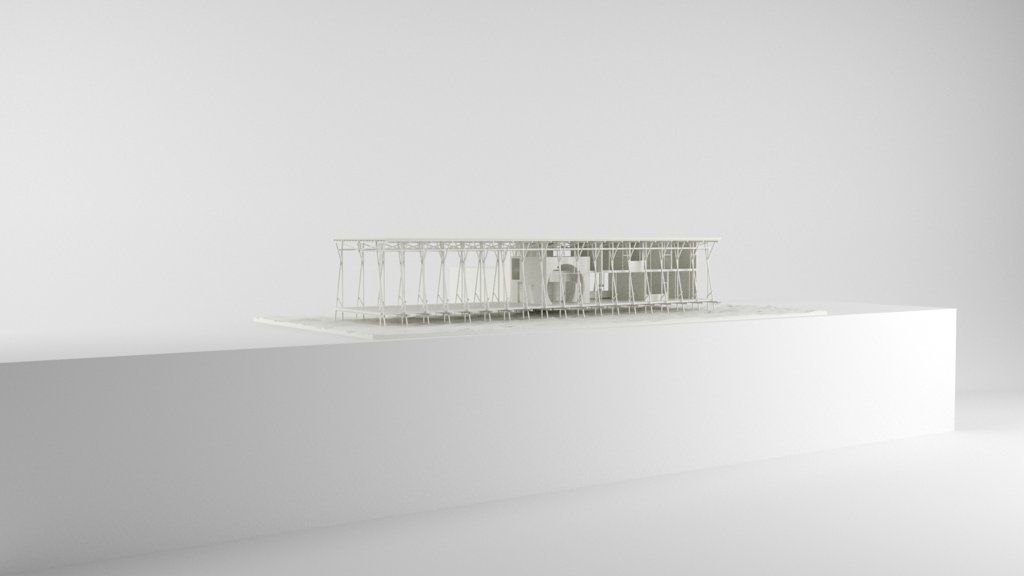

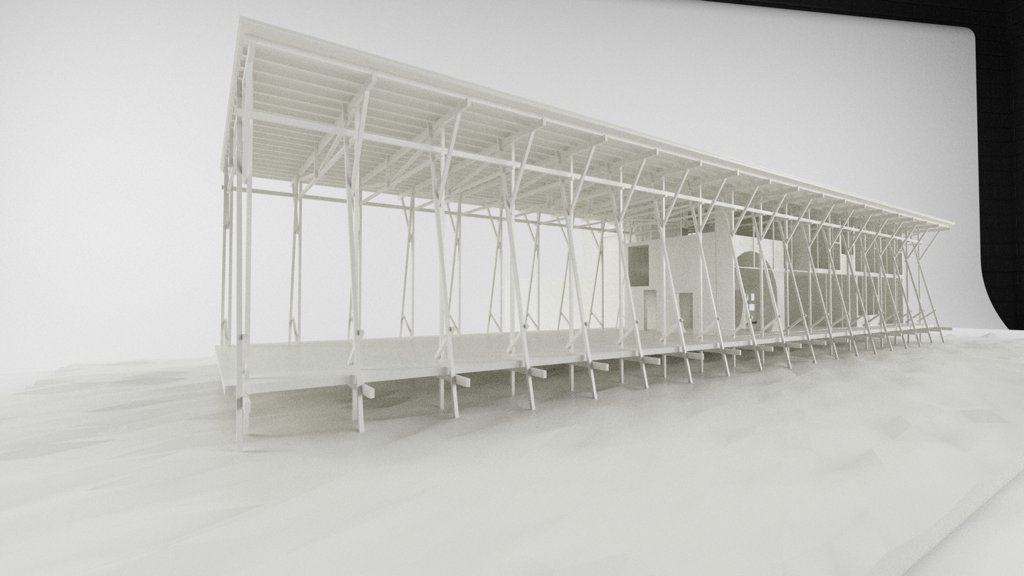

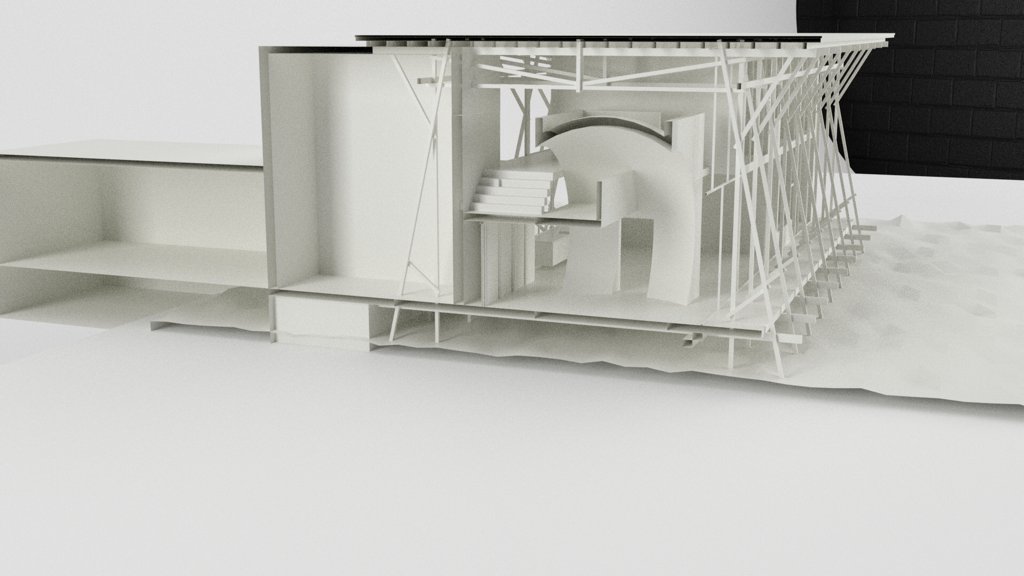

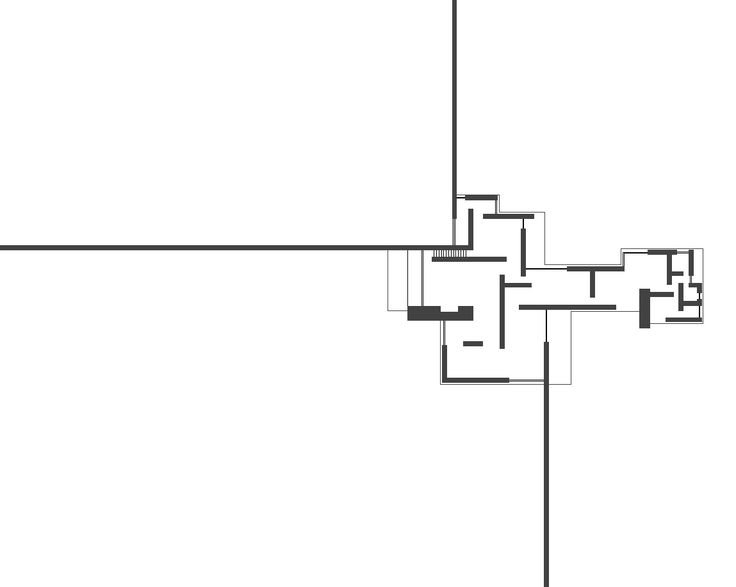

Anyway back to the present... Eisenman was talking about the importance of the plan and aggregation — how he layers various geometries to form an unorganised whole which critically says something about existence...

About thirty years ago I had a great teacher (there have only been two so far) called Travis Isherwood. God only knows why such an intellect was teaching at Salford Tech. I was only sixteen on a foundation course in art and design. He taught me many things including life drawing and he could actually draw, I mean really draw, or see as he would put it. For his education he'd spent four years life drawing, every day at the Royal Academy. He was about sixty, so traditionally trained. He taught me about Michelangelo and Leonardo and Ingres and Picasso, he knew everything there was to know about Art and History.

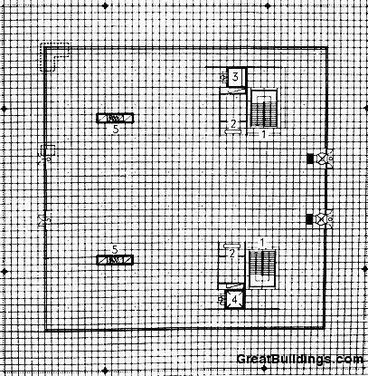

He treated me like I was an idiot and would laugh mercilessly at my misunderstanding of everything he would blow my mind with. He wore a black eye patch and would cackle like an old pirate. But I didn't care one bit, all I wanted was access to the secrets of the universe I'd craved all my life. You see he didn't just know about Art, his main interest was Architecture. He'd sit for hours demonstrating how Le Corbusier's Modular proportional system could be used to determine the most functional height for a chair and how it encompassed the Golden Mean, function and aesthetics fused. He told me about the Greeks and the Parthenon and its connection with Le Corbusier. I heard for the first time 'Less is more'. 'My God' I thought, of course 'Less is more'... In the back to backs of Salford Architectural Philosophy isn't really discussed!

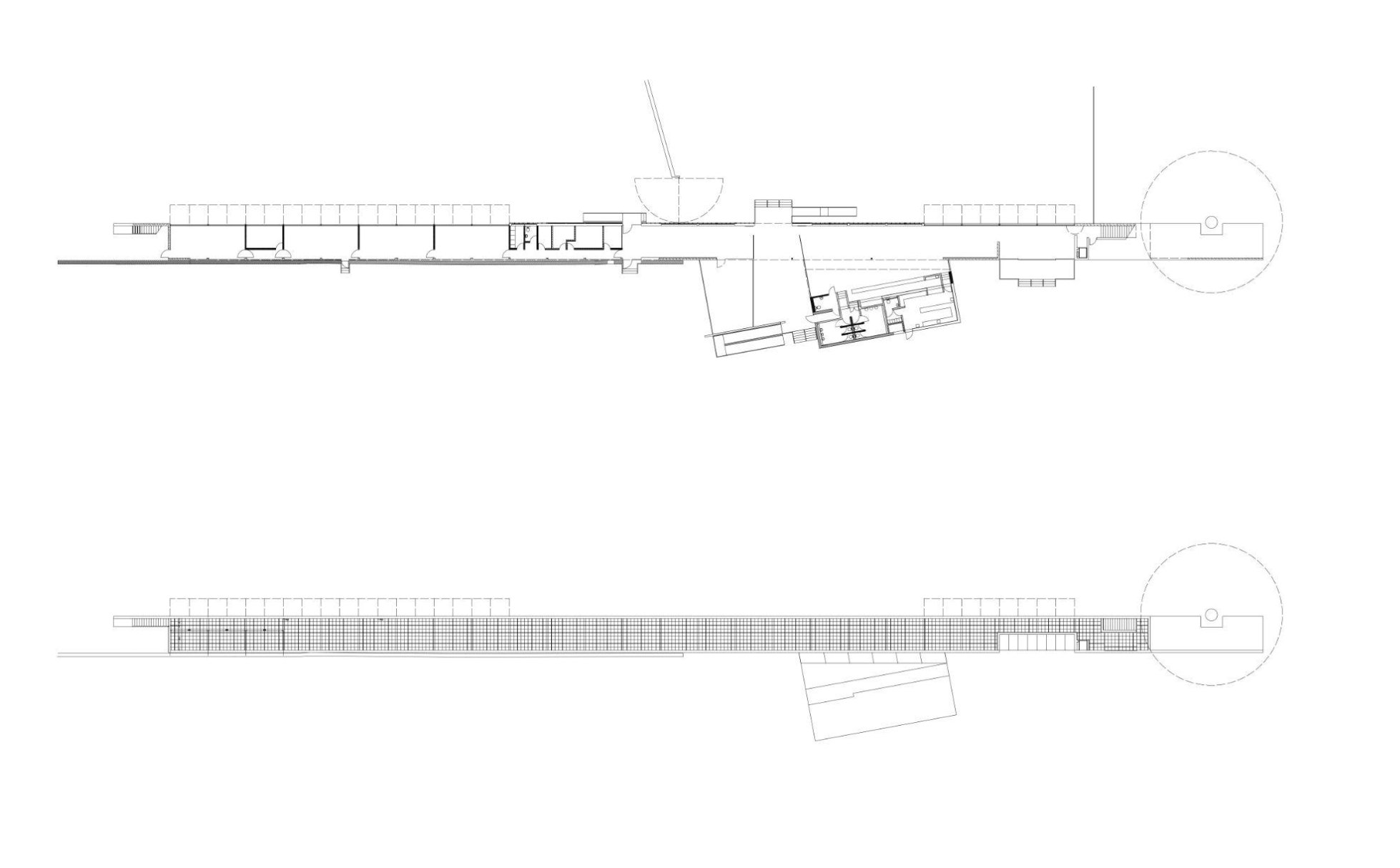

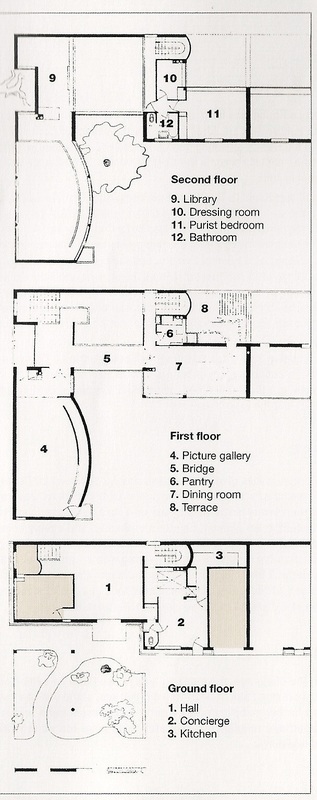

The 'Plan is the generator' Travis said, quoting Le Corbusier, this is the sentence I was reminded of from thirty years ago.

This is kind of what Peter Eisenman was saying — although he sees it in a different way which involves lots of French philosophy which is very difficult to define. My simplistic interpretation is that it's something to do with the convention of the plan as an internal logic belonging to the Discipline of Architecture with a capital 'A'. As if the plan is a formal, critical tool which can be used to unlock the meaning of Architecture as a Metaphysical Project — is it really there? and, if so, what is it?

My interpretation at the age of sixteen was given away by my response: 'So do you mean you can feel the plan when walking through a building?' I asked. Eisenman would hate this response. He is at war with Phenomenology. And I think for all the right reasons. Although I love the fetishisation of materiality, as I love Zumthor's work, I still want Architecture to be about the discipline. A culture with History/Time and syntax. It's just too fascinating — to only think about the sensory experience of a building seems far too easy.

And if you look at Jacques Derrida whose Deconstruction philosophy is a part of Eisenman's investigations, his aim was to reveal Truth by deconstructing the very context of a system — the binary oppositions set up to form an idea. Or what some Modern Spiritual thinkers call 'This and that' or 'The relative world of opposites'.

So yes I'm back to the mystery which 'Everybody knows' and can only be not talked about by talking about something. The something is the plan.